Method

“So blind is the curiosity with which mortals are obsessed that they often direct their energies along unexplored paths, with no reasoned ground for hope, but merely making trial whenever what they seek may by happy chance be thereby found”. – Descartes

It is in human’s nature to wonder around without defined paths, it is a property of the human mind not to follow a set of rules; unless a force is applied to keep it fixed on a definite path. Most humans do not follow a fixed path, a method, but pick up the left-over of passers-by. Men always hope to gain, but with the desire to put the least of efforts; they want the treasure to come to them, the same way we want money to come to us with the least work possible; we want recognition with the least of struggle. It is possible to attain such realities, but they are not a product of self-determination, of self-control or of following one path (one method); they are the products of fortune, of luck. Putting it in Descartes’ words “I am not denying that in their wanderings they sometimes happen on what is true. I cannot, however, allow that this is due to grater address on their part, but only to their being more favored by fortune.”

If lost in a jungle, it is much better to follow one path, than to change from one to another; the lack of knowledge (of which path leads you where) may end up bringing you to the same point over and over again. To find the truth is like finding the way out thought the jungle; following one path (one method) has more chances to get you out than the chances you have from jumping from one path to the other. It is far better not to have desire to seek the truth than to do so without method. For, what is quite certain is that unregulated studies and confused mediation tend to puzzle the natural light, blinding the mind. To gain knowledge is to know the truth, to be beyond doubt. All of us have undergone schooling, but it is this schooling the cause of all our confusion. There is no single matter, in whatever we have been thought in our many years of schooling, on which wise men agree; nothing which is beyond doubt, for how can this be knowledge?

To gain knowledge (the truth) a method is necessary, Descartes believed, a set of rules which need to be followed all the time. For Descartes method meant “rules which are certain and easy and such that whomsoever will observe them accurately will never assume what is false as true, or uselessly waste his mental efforts, but gradually and steadily advancing in knowledge will attain to a true understanding of all those things which lie within his powers.” Descartes believed to have discovered one method which leads to the “truth”. He did not deny the existence of other methods but he believed that his method, which worked for him, leads to the truth and wanted others to have the opportunity to use this method. His method consisted of four rules:

Rule 1

“Never to accept anything for true which I did not clearly know to be such; that is to say, carefully to avoid precipitancy and prejudice, and to comprise nothing more in my judgment than what was presented to my mind so clearly and distinctly as to exclude all grounds of doubt.” – Descartes

Prejudices are a product of information which has been imparted on us. We have all learned much in our years of schooling but have we gained knowledge? Knowledge is beyond doubt, but in whatever we have learned there is no single matter on which wise men agree upon. There is no such matter which is not under dispute. “He who entertains doubt on many matters in no wiser than he who has never thought of such matter”. It is better not to study at all than to occupy ourselves with objects so difficult that, owing to inability to distinguish true from false, we may be obliged to accept the doubtful as certain. In such enquiries there is more risk of diminishing our knowledge than of increasing it. No modes of knowledge which are probable are acceptable; only that which is perfectly known and in respect of which doubt is not possible can be considered knowledge. All such matter which involves “probable opinions” is to be ruled out as a base to acquire “genuine knowledge”. What is then genuine knowledge, what is known to be beyond doubt? In Descartes’ words “Accordingly, if we are representing the situation correctly, observation of this rule confines us to arithmetic and geometry, as being the only science yet discovered.”

Rule 2

“To divide each of the difficulties under examination into as many parts as possible, and as might be necessary for its adequate solution.” – Descartes

What is unknown can only be understood in relation to what is known; nothing is completely unknown; for if it were, it could never be known. The prerequisite to attain knowledge is that we are, from the start, is possession of all the data required to find the truth. To find the truth there, firstly, must be in every question something not yet known, other wise the enquiry would be to no purpose. Secondly, the not yet known must be, in some way, marked out; otherwise our attention may tend to deviate towards something else. Thirdly, the unknown can only be marked out in relation to something which is already known. Thus, if we are asked to find what is the nature of a magnet, we already know what is meant by those two words, ‘magnet’ and ‘nature’, and thereby we are determined to enquire on these two words than on something else. But over and above this, if the question is to be perfectly understood, we require that it is made so completely determinate that we have no need to seek for anything beyond what can be deduced from the (already known) data.

Rule 3

“To conduct my thoughts in such order that, by commencing with objects the simplest and easiest to know, I might ascend by little and little, and, as it were, step by step, to the knowledge of the more complex; assigning in thought a certain order even to those objects which in their own nature do not stand in a relation of antecedence and sequence.” – Descartes

The third rule can be understood as a process of “analysis and synthesis”; a digging to the bottom rock (analysis) and a reconstruction of the structure from the bottom (synthesis). It is about distinguishing simple things from the more complex ones and arranging them in such an order so we can directly deduce the truths of one from the other. This rule admonishes us that all information can be arranged in certain series, not classified as categories, but in order in which each item contributes to the knowledge of those that follow upon it. There are two different relation which can be found while digging: the ones at the rock bottom (the absolute ones) and the on the way to the bottom (the relative ones).

Absolute is that which possesses in itself the pure and simple nature of that which we have under consideration, i.e. whatever is viewed as being independent, cause, simple, universal, one, equal, like, straight, and such like. These are the simplest and easiest to apprehend and they serve to find the relative one; the search is always from the bottom to the top. The relatives share some properties with the absolutes, since they are deduces from them, yet they involve in its concept, over and above the absolute nature, certain other characters i.e. whatever is said to be dependent, effect, composite, particular, multiple, unequal, unlike, oblique, etc.

The above rule requires that these relatives should be different from one another, and the linkage and the natural order of their interrelations be so observed, that we may be able, starting from that which is nearest to us (as empirically given), to reach to that which is completely absolute, by passing though all intermediate relatives.

Rule 4

“To make enumerations so complete, and reviews so general that I might be assured that nothing was omitted.” – Descartes

The search for knowledge is not easy, many are the question which will have to answered, some will be known and some not. Some of the truths which we have been seeking of are not immediately deduced from the primary self evidencing data; this deduction sometimes involves series of connected terms arranged in a sequence. The process is long and this is why it is not easy for the mind to remember all the links which it did to conduct us to the conclusion. Continuous movement of thought is required to remedy this weakness of memory. One should run over each link several times and this process should become so continuous that while intuiting each step it simultaneously passes to the next one; this process should be repeated until the mind learns to pass from one step to the other, so quickly, that almost none of the step seem to exist independently but the whole process seems a “whole”. This process of deduction should nowhere be interrupted, for even if the smallest link misses the chain brakes and certainly the truth will escape from us.

This whole process relies on enumeration. In all questions there is something (however minute or however negative) which may escape us, and only by enumeration can we be conscious of leading a correct induction. Only by the means of enumeration can we be assured of always passing a true and certain judgment on whatever is under investigation.

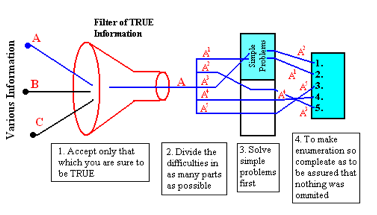

Diagram of the four rules.

This diagram is a pictorial representation of the four rules. Many in formations are given to us by the outside world, but (as the fist rule states) only those which are sure to be true must be accepted. The filter which is shown is like an imaginary organ in our brain which allows only true information to go tough it. Information “A” is true and is allowed to pass; this information must be then divided (rule 2) in as many parts as possible. Once the information is divided we need to classify it in two different categories (rule 3): the simple problems (those which are in an absolute relation) and the more complex problems (those which are in a relative relation). First the simple problems are solved and as we are able to solve the simple questions we come to the more complex ones any try to solve them. Finally to check that we have not missed even the smallest link (rule 4) between each link which we have made, we enumerate all the information and recheck all the links.

Conclusion

Descartes is known as one of the major philosopher to have conceptualized modern philosophy; to have brought “philosophy” from “a way of life” to an academic subject and his main focus of interest was “knowledge”. What is knowledge? How can we attain knowledge, if we can attain it at all? To question everything (method of doubt) was for him the first step towards knowing the truth; truth which he considered to be knowledge.

The four rules, above explained, were for Descartes the path which led to the “truth”. We cannot deny the success which Descartes achieved by using this method, since he claimed that it was by the use of this method that he discovered analytic geometry; but this method leads you only to acquiring scientific knowledge. What I believe, any many others also do, is that what Descartes meant by knowledge is what we now call “scientific knowledge” and scientific knowledge is only a sub-category of knowledge, not knowledge as a whole.

Hey there, could you tell me what all books have you referred to (if at all) apart from The Discourse on Method. Very neat write-up there, also on a slightly different note, added you on facebook..just to make it little less awkward and discuss while I drudge along college (if you don’t mind).

–

Aniesha

can’t really remember where i got the reading from. a bit of the book, some class notes, some prof’s readings, etc… 😀